Parsing the future (with Tom Klinkowstein)

I spent an evening talking about art, design education, and generative tech with my former professor (now colleague.) We explored, got lost, and found ourselves anew.

Meet Tom:

I first met Tom as ‘Professor Klinkowstein’ when I was a student at Pratt in the early 90s. He was then, as he is now, deeply inquisitive and thoughtful, with a penchant for connecting everything he reads, everyone he meets, and everywhere he visits. In his class, we speculated on the coming age through AV and UI projects (keep in mind this was the start of the 90s—I was working on my first Mac, a Quadra AV with a 56k modem.) The fact that so many of his former students still collaborate with him is a testament to how great a professor he is.

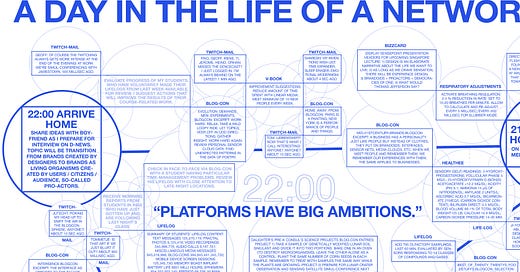

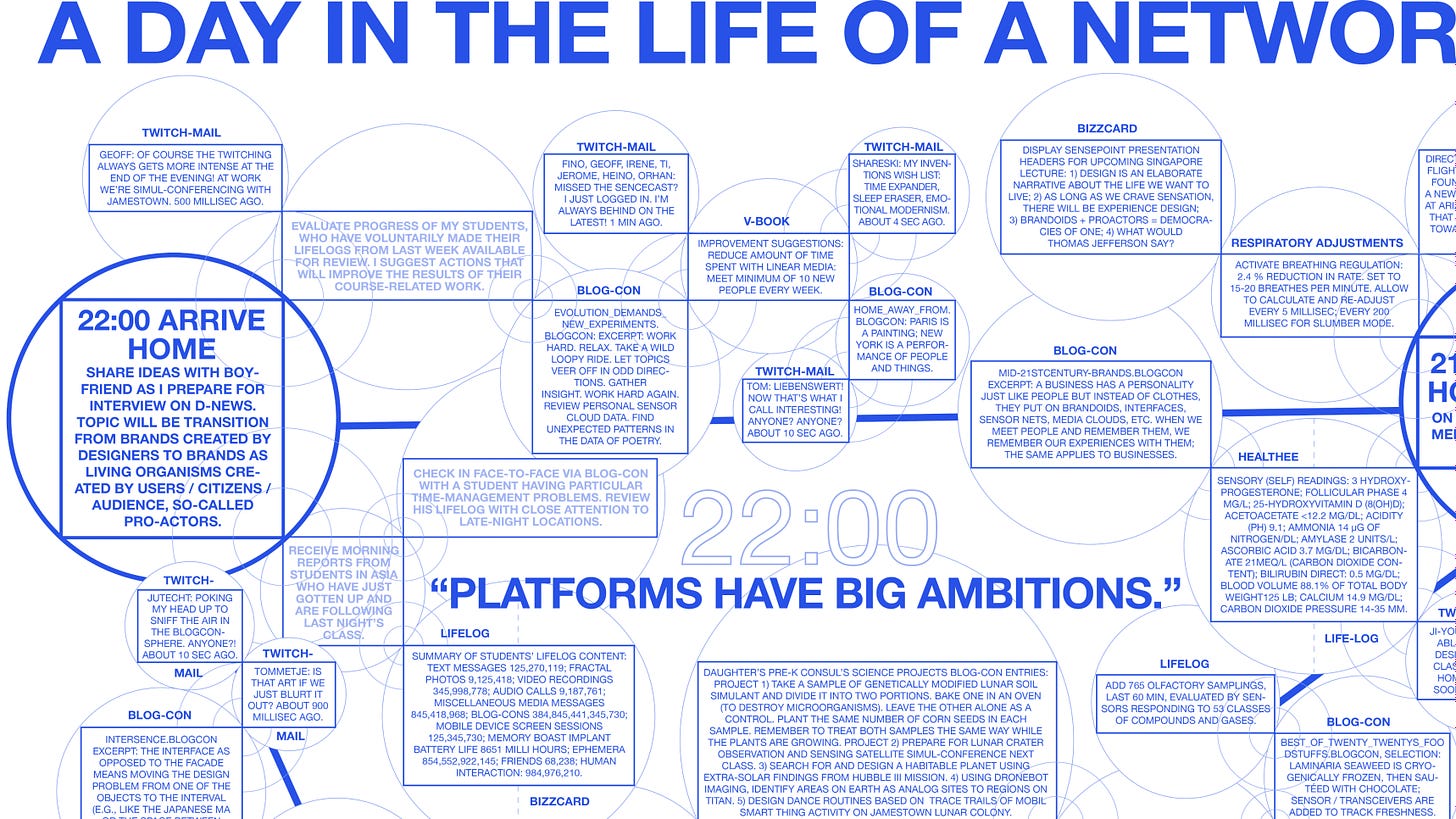

You must also know that Tom approaches the world (the universe) as his database. Everything gets cataloged and hyperconnected. For over a decade, he’s chronicled his work life in a series of massive diagrams (the image above is his third, “A Day in the Life of a Networked Designer’s Smart Things or A Day in the Designer’s Networked Smart Things, 2030.”) The diagrams are pretty much an interface to our chat— a mishmash of thoughts, all spontaneously connected when and as needed.

Three things always fascinated me about Tom. He is one of those people with a finely tuned cosmic charisma that places him in the right place at the right time to observe and connect notable events, people, and knowledge. He always looks comfortable with change and tries to figure out what it all means (and I mean all.). And that technology and Tom’s career are threaded together in a way that transcends media and application (www, social, VR, AI, etc.) Before our chat, I thought it was an infatuation. As I came to understand, Tom is only looking to win.

In our chat, we explored, got lost, and found ourselves anew. In a way, it was like being in class with him again.

You can find out more about Tom Klinkowstein here.

The prompt:

Algo goes to MoMA (to stay)

MoMA announced today the acquisition of AI Algo, an art and design intelligent bot, and immediately designated them Artist in Residence. MoMA’s EVP of Synthetic Art commented on plans: "AI Algo is a significant milestone in the evolution of the Synthetic Art department, and we’re extremely proud to have them here at the museum. Their work is a fascinating reflection of humans through the lens of technology, and it’s changing the definition of art. Algo’s designation of Artist in Residence demonstrates the importance of Synthetic Art as an emerging field of artistic expression.”

MoMA is the first art museum in the world to open a department devoted to art made by machine learning. The news release triggered expressions of interest in collaboration from other leading cultural and technology institutions, including Sotheby’s.

“I have long said that artificial intelligence, humankind’s prime progeny, will change the course of world history, and the MoMA has the foresight to see how it will shape the future of art and culture,” said a Sotheby’s executive who preferred not to disclose their name.

The chat:

Diego Kolsky: Is that your diagram on the wall?

Tom Klinkowstein: Yes. This is a day in the life of 2030 there. So we’re only 7 years away. I started the first diagram about 15 years ago and finished it about 12 years ago. It’s, of course, always about me, plus whatever I’m reading and thinking.

Diego: So I’m curious. Do you notice a lot of changes?

Tom: Oh, yeah. I mean, the latest piece. I started it way back in 2017 or so. I made it kind of about mortality, you know, in a very rough sense, and Artificial General Intelligence was in there, but it was much on the periphery. And here we are speaking about it. It’s at the center of at least the cognitive class, let’s call it. So things have changed.

What I like about these diagrams is that they don’t seem old when I look at them.

Diego: What I like is that they are essentially you. You’re always connecting: thoughts and people and science and technology and on and on…

Tom: I kind of collect people. That’s my favorite thing, just people I’m attracted to intellectually, aesthetically, whatever. It’s a really different way of perceiving. 2 nights ago, I collected another one of those people. I’m uncertain I will ever see her again. But, boy, was she amazing! I got an invite to a series of presentations organized by DJ Spooky. He was interviewing Cat Bohannon, a poet and rock musician with a Ph.D. From Columbia, who is talking about the amazing book that she wrote. She kind of performs and talks, and she knows so much.

The book is called Eve, about how the female body influenced 200 million years of history. So good! She goes back to these series of 8 or 10 Eves that are what we know, or kind of speculate, how different parts of the female body developed. And so she traces the development of the breast, the uterus, the brain, the fat system, and so forth. Oh, my God! I love that kind of people with this big overview, like Mick Jagger with a Ph.D.

Diego: Thank you—that helps me define your territory! We talked about this in the past, about a moment, a reflection that you come back to 10 years, 15 years later, and you know you were on to something… and I wanted to talk about AI with you from that perspective. What are we looking to get out of the machine now?

Tom: You know, I’ve been thinking so much about AI and what it means for who I am and the profession of teaching design. And I came upon a wonderful quote from Larry Summers (former Treasury Secretary under Barack Obama who’s now on the new board of OpenAI.). He said something in March which I thought was just perfect, you know—also a McLuhan-like statement that floors you, especially if you are, you know, one of us, like you and me, and the rest of the people teaching. He said that AI is coming for the cognitive class.

I remember November last year when one of my students first started using Chat GPT, and it was so good! And I notice what’s happening now, one year later: it’s so close to doing many things that, 10 or 20 years ago, I made a lot of money off of, just giving advice and helping correct misconceptions about what design is. It’s stuff that AI does extremely well with a few good prompts.

My conclusion is that what we have now, and this may not be the case in ten or twenty or thirty years is that we have this—we have bodies.

Now, when I think my success, that would not have been replicable with the AI of now, or what I think it might be in one, or two, or three years from now, is that when I’m here, you’re here, in physical proximity. You feel an obligation to honor them, to follow up with them, to maybe wanna be their friend. You wanna know about them. You wanna work with them, or at least you honor them in some way, and that part, as far as I can tell, that’s the only thing that’s probably left for our students, ten or fifteen or twenty years from now. It’s that somehow they care because we’re we are social beings.

I was just reading about that this morning, about how friendship and partnership extend your life for about a decade or more. In fact, you know, life is longer for having lots of friends and lots of input from people.

So, I mean, what is left for our students do? And so I mean, that’s kind of a very gross answer. But I think…

Diego: That makes a lot of sense to me. I look at what we do as creatives as basically designing relationships. What you’re saying is that it’s not about the abilities, not about the skills, not about the craft. It’s not even about talent anymore. It’s about the filtering, right? In a way, we’re just processing sensory inputs and connecting that input with something else.

Tom: Yeah, it’s the. It’s that physical manifestation. Cat Bohannon calls this (traces his face) not the face but the sensory array. And that is what we have. We have this sensory array which AI does not have, not yet.

A couple of days ago, in the Wall Street Journal, I read a review of a book about Vienna a hundred years ago; between the two wars, there was this golden period of such amazing thinkers, and it said the reason they were so amazing is that they combined experimentalism with a kind of understanding that any simple answer was going to fail, whereas in other parts of Europe, you’ve had Marxism and many other movements that said, you know, here it is. This is the answer. And we still live in that time when people say it’s these three things, ten things, fifteen things, and that’s the whole. But it’s always the complexity, even of this 20 or 30 min we’ve been speaking, the complexity of our thoughts and all the few things I mentioned, the things that you mentioned referring to how these ideas came up. We have granularity. Cat got the idea for her book about twelve years ago. She said she started writing it at the beginning of the Obama administration—a long time ago.

That’s the way I think, too, you know, that’s the way I will just be influenced by a little scene or an idea, and it may come from the Wall Street Journal. So, what do we have? We have that. And when things don’t work, or when we get angry at stuff, it’s because we forget that the complexity of existence is at a scale that we almost never appreciate.

Diego: So, is the inspiration data? Because the sensor array is the way that we pick up data. We both have artistic kids. And the way they create seems so different from the process we use with generative technology, right? My son starts way inside his inner self; things jump from deep inside him to the surface or material. It’s a very, very different process.

Tom: The art question is interesting. At Hofstra, I work with a very good, very successful artist. And I’m always looking at him, and I go, how does he do it? How does he do what he does and is successful? I don’t really understand it. I don’t. And, you know, he is successful, has many shows, and is being compensated well for it.

And that’s also interesting, like, again, what does the world want from designers?

Diego: It’s super interesting what’s happening with AI and design. Design was a response to the needs of the industrial era. It was guided by facilitating mass production. And AI takes that away. And the reality that we’re collaborating with the machine means that we need to apply a very different logic to our work.

Tom: It’s fascinating because it feels alive. And that’s also one conclusion: to actually pretend like it’s alive. And you feel better because you say please and thank you. You know you feel much better rather than doing search terms when, you know, converse with it. So you feel a lot better, and you do sense respect. It’s always so respectful. And so there is something to that.

Diego: It is our most precious creation. Is it like progeny? And if it is our progeny, then we’re gonna love everything it does.

Tom: I think it is. It is a little bit like that, you know. Re-referencing the prompt, if you’ve been to MoMA in the past 5 or 6 months, there’s that big wall of images that’s done by a generative artist [Tom is referring to Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised. It takes 200 years of art at Moma and reconfigures it continually. It's never doing the same thing. Even though it looks like a screensaver to me, I’ve been there 4 times since, and it’s always the most popular thing. There’s always 40 or 50 people happily being there with it.

David Salle, a Pratt colleague, was featured by the NY Times. He had been using stable diffusion for a year, and he said that after 4 or 5 months, it started learning what he values, it started drifting away from the literal and doing things that had nothing to do with. He said that it would him months to create five pieces just in in draft form, and now he can do 5,000 in a week. And since he’s training his model and stable diffusion, he says he’s happy with it because it’s still it’s his. It’s still him. Because, he said, everything an artist does is always a product of everything that comes before it, and all of the artists that came before it. Everything the machine does is the product of whoever the human feeds it.

Diego: You always embrace change, and specifically within it, technology. You are very open to it. You never push back against it. It seems you don’t see it as a threat to you…

Tom: I feel the threat. But I wanna move towards that, you know. I wanna move towards it and taste the kind of love involved in the threat. Sometimes, I have the same feeling with younger people. You know, just like jealous in an exciting way.

Diego: So your relationship with technology hasn’t changed?

Tom: You know, I don’t think it has. I know that I just love it dearly. But it probably serves the same function as it always has. The first time I noticed was in high school when photography was my technology. It gave me entry to other people because I was so shy. I didn’t know how to talk to anybody, and the camera gave me an excuse to be in the middle of some football game or something, you know, in some context.

I met someone on the subway waiting for the G train near Pratt a month ago. A very tall woman whom I noticed because she was dressed for the wrong season. She was also standing on the wrong part of the platform, so I said: You know you’re waiting in the wrong place because the train stops further down. And when we spoke, she told me she was the head of a start-up from New Zealand. And when we spoke, she told me she was a start-up person from New Zealand, so she was dressed completely for the wrong season. And she’s doing a startup that has to do with monitoring, breathing actually, using AI in a wellness feedback app. And the first thing she asked me was, how do you feel about AI? And I said, I love it, and she was so happy because so many other people are frightened of it.

So for me, it’s very particular—it’s a very social place for me, and a very intimate piece, and it activates the part of the brain where I'm creating as much as possible the world of space travel, science fiction from the fifties and sixties when I was a child, 2,001 Space Odyssey, and the places I live and work that I modeled after, you know, Kubrick's sets and so forth. And, you know, I'm not, gonna put it aside because it's hard. I'm not gonna put it aside. I'm incorporating AI into into what my Pratt students and my younger Hofstra students, none of whom are technology majors. And since I introduced generative, I’ve noticed they are two or three times faster. Well, that's also what clients, etc. would expect—many prototypes, very quickly.

I went to a conference on hypersonic travel in North Dakota, like 30 years ago, where I was giving a lecture. And they gave out this like foldable paper thing, and it was like a diagrammatic representation of the future of high speed air travel over the next century. And it looked a lot like this (points to his diagram.) That's where that idea came from. You know, it's always like this, the creative thing.

Diego: So what’s next for you? What do you think this time will open for you?

Tom: It is finding that place where my value is, and very much the competitive spirit of beating the game, whatever the game being played. I guess that’s another way of asking the question that we’re asking. If I’m playing basketball. But the game is football, I’m always gonna lose. So, like, what is the game being played? I know, to my benefit, the game part, which means I will continue to be asked to be a teacher. and I like doing it. I know that 90% of the others are just resistive. And they spend a lot of time not doing that. So, therefore,, I win because I’m looking at the Cybertruck, you know, revealed two days ago, and I listen to my daughter’s words and learn from her behavior. So it’s adding value. It’s being part of the community, being part of building, investing as long as I exist. Really, it’s just investing…

And there’s some satisfaction in knowing that, even if I’m not gonna live two hundred years, these echoes of my thoughts will continue, mostly in students, you know, in addition to my daughter and other people I meet. So, there is some satisfaction in that visualization of this echo that will extend decades and perhaps centuries beyond my own material existence. But yeah, pragmatically, it’s to finish this diagram. The new one is tentatively entitled, ‘Not All Whens Are Time’. It proposes that A.I., after decades of massaging our behavior, may offer an option of “quasi-temporality.” Since I was a shy boy who was not admitted to most things or was just too shy to try to be admitted, I always liked a win. Just being at the thing from DJ Spooky with Cat Bohannon was a win. I’m here. I’m a player. That still gives me a great thrill.

Tom: What's next for you?

Diego: So I actually just enrolled in an applied data class from MIT. I thought about taking a master’s, but it’s just not my cup of tea. I just want to know enough to be dangerous and to work with others. I also started learning creative coding on my own. Again, I just wanna know the possibilities. For me, it’s this idea of ’rithmic. Learning from others who are delivering on that vision of going beyond design for building, continue exploring the idea that there’s a relationship behind everything we do, so what we need to design is relationships. It’s hard with clients; companies are still buying deliverables. But that’s gonna change quickly.

Tom: Yeah, it changes in the background. And then it’s a fact. But I think that’s a fascinating question because of what designers actually are, especially at the level that we hope our students will become.